|

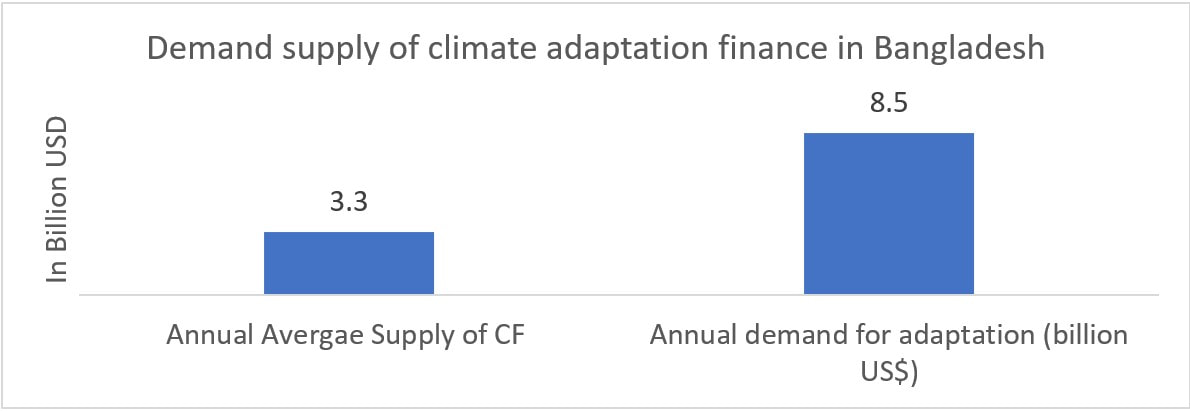

By M. Zakir Hossain Khan* and Shadman Khalili** The escalating climate crisis poses an existential threat to Least Developed Countries (LDCs), exacerbating existing vulnerabilities and jeopardizing their development progress. A recent temperature spike of 38.5°C in Antarctica, the coldest place on Earth, raises fears of catastrophe and serves as a harbinger of disaster for humans and the local ecosystem. Article 9.4 of the Paris Agreement states that financial resources should aim to achieve a balance between adaptation and mitigation. The Green Climate Fund (GCF) reflects this aim with its 50:50 provision for both activities. Considering country-driven strategies and prioritizing the needs of developing country parties, especially those that are climate-vulnerable (e.g., CVF) and have significant capacity constraints, such as Least Developed Countries (LDCs) and Small Island Developing States (SIDS). Public and grant-based resources are crucial for adaptation in these countries. While a universal definition of climate finance remains elusive, there is no doubt that adaptation is crucial for the survival and sustainable development of LDCs. However, they face a significant financing gap that hinders their ability to implement effective climate resilience strategies. The Widening Adaptation Finance Gap: A Stark Reality The adaptation finance gap is a staggering 10–18 times larger than current international adaptation finance flows – a significant increase of at least 50% from previous estimates. The UNEP's Adaptation Finance Gap Report 2023 highlights this critical issue. It estimates annual adaptation costs for developing countries to be between US$215 billion (roughly $660 per person in the US) and US$387 billion (around $1,200 per person in US dollars). This stands in stark contrast to the meager US$21 billion (approximately $65 per person in the US) received in international public adaptation finance flows in 2021, representing only 5% of the estimated needs. National Determined Contributions (NDCs) and National Adaptation Plans (NAPs) suggest a per capita adaptation finance need of US$55.3 (based on the US$387 billion estimate) per year for 2021 to 2030. However, international public adaptation finance flows only reached US$3.08 (based on the US$21 billion in 2021) – a concerning 15% decrease from 2020's allocation. Unfortunately, over the last decade, climate finance (see more details in questions 3 – 5) has mostly been provided through debt creating instruments. Continued use of loans to fulfil climate finance obligations sharply reduces a country’s ability to achieve fiscal stability and debt sustainability and helps to fuel the debt crisis in the global south. This is the opposite scenario to climate justice and sustainability of nature. Despite pledges made under the Paris Agreement to mobilize new and additional to ODA (mostly grant), including the goal of doubling adaptation finance by 2025, progress remains woefully inadequate. Even achieving this target would only make a modest dent in the adaptation finance gap. Concerns are amplified as the V20 group of highly climate-vulnerable countries struggles with a crippling debt burden, further limiting their ability to invest in adaptation. Climate change exacerbates this challenge, with climate-related losses between 2000 and 2019 estimated at US$525 billion – equivalent to 76% of the V20's debt stock. This creates a vicious cycle: debt hinders climate action, while climate impacts further worsen debt burdens. However, a significant hurdle for LDCs in accessing grant-based adaptation finance remains the complexity of application procedures, stringent eligibility criteria, and bureaucratic processes. This system disproportionately disadvantages smaller nations and local organizations, exacerbating the marginalization of those most in need. Furthermore, the current emphasis on project-specific grants often neglects the critical need for long-term resilience, institutional strengthening, and holistic adaptation strategies that address systemic vulnerabilities. Additionally, existing financial mechanisms fail to adequately incentivize private sector investment in adaptation, leaving a vast untapped resource for climate action. Moreover, the lack of comprehensive data on adaptation finance flows and needs hinders effective planning, resource allocation, and impact assessment. A Call for Transformative Actions Dominant Sources and Needed Reforms:

Unlocking Private Sector Investment:

Scaling Up Public Funds and Streamlining Access:

Building Long-Term Resilience:

Knowledge Sharing and Local Ownership:

A Collective Responsibility for a Sustainable Future Addressing the adaptation finance gap is not just a financial challenge; it's a moral imperative and a critical investment in our shared future. Least Developed Countries (LDCs) bear the brunt of the climate crisis, despite lacking the resources to adapt and build resilience. Grant-based climate finance plays a significant role in supporting LDCs' adaptation efforts, but its current scale needs a significant increase to meet growing challenges. The international community must act urgently and decisively to scale up adaptation finance, equip LDCs with the tools they need, and foster a global partnership for climate action. By investing in adaptation today, we can build a more just, equitable, and sustainable future for all. The cost of inaction will be far greater, leaving a legacy of devastation for LDCs and the entire planet. Let us rise to the challenge and ensure that adaptation finance becomes a cornerstone of global climate action, securing a resilient future for LDCs and the world. * Chief Executive of Change Initiative and International Climate Finance Expert; email: [email protected]

** Manager, Change Initiative

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |